1935 began with a letter from Kline to Howard, dated 28 Jan

1935; Leo Margulies rejected a synopsis for “The Silver Heel,” a Steve Harrison

detective story, and Kline suggested they might try it on Roy Horn’s Two-Book Detective Magazine; though if

they did, nothing came of it. (IMH 23) Kline gave a few of the Dorgan

rewrites to his employee Miller to market, without apparent success. (IMH 369) Then on 13 May 1935 there was a

letter from Howard to Kline:

I’m writing this to ask for some

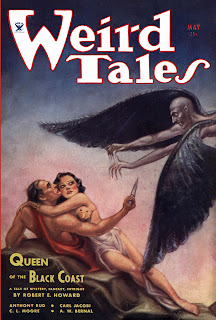

information in regard to Weird Tales.

As you know, for some time I’ve had a story in almost every issue. One of those

yarns you sold Wright, yourself, “The Grisly Horror,” you remember. The others

I sold him direct. For over a year, as I remember, I’ve received just half a

check each month — just barely enough to keep me alive, but I didn’t kick,

because I knew times were hard, and I believed Wright was doing his best to pay

me. But this month there was no check forthcoming — and this check would have

been much bigger than any check I’ve gotten for a long time from Weird Tales. I wrote Wright, telling him

the trouble I’d been in, and explaining my desperate need for money, and up to

now he’s coolly ignored my letter. No check — and not the slightest word of

explanation. The case is simple enough: Weird

Tales owes me over $800, some of it for stories published six months ago.

I’m pinching pennies and wearing rags, while my stories are being published,

used and exploited. I believe Wright could pay me every cent he owes me, if he

wanted to. But now, when I need money worse than I ever needed it in my life

before, he refuses to pay me anything, and ignores a letter in which I beg him

to pay me even a fraction of the full amount. What’s his game, anyway? Is Weird Tales still a legitimate

publication, or has it become a racket? Of course, anything you tell me will be

treated as confidential, just as I expect this letter to be treated. I don’t

want to cause anybody any trouble or inconvenience. But Weird Tales owes me something like $860 and naturally I want to

learn, if I can, if there’s any chance of ever getting paid. (CL 3.308-309)

Howard wasn’t alone; the Great Depression hit Weird Tales and the other pulps hard,

and there was likely nothing Kline could do, except tell Howard he wasn’t

alone—Kline himself was still selling stories to WT, including the serial “Lord of the Lamia” (Mar-Apr-May 1935).

Whatever Kline’s response, Howard appeared to find it acceptable, as he wrote

to Emil Petaja:

I have found him very satisfactory in

every way, and do not hesitate to recommend him. (CL 3.369)

One of the selling points of Kline’s agency was foreign

sales, and in 1935 it appears, after a good-faith effort to move stories in the

United States, he tried to place them in Canada or the United Kingdom; Howard

already having had a few stories published in the UK

Not at Night anthologies before Kline became his agent. The stories

included the Dorgan yarns, “Swords of the Hills,” “A Gent From Bear

Creek,” “The Voice of Death,” “The Names

in the Black Book,” “The Grisly Horror,” as well as “Hawks of Outremer,” “Jewels of Gwahlur,” “Beyond the Black River,” “A Witch Shall Be Born,” and “Red Blades of Black Cathay,” (a collaboration with Tevis Clyde Smith). (

IMH 358, 360, 362-363, 364-365, 366,

367, 369-370, 371) None of these stories sold in foreign markets, but Howard

had also prepared a stitch-up novel of his Breckinridge Elkins stories, and

Kline wrote in a letter dated 8 Oct 1935:

I recently had an inquiry from an

English publisher on four Western novels submitted to him some time ago. It has

occurred to me that it might be well to offer than a carbon copy of your novel A Gent from Bear Creek. The American

publisher who is considering the original has not yet reported. (IMH 31)

Kline also encouraged Howard, like E. Hoffmann Price, to

“splash the spicies.” Edited by Frank Armer (of Strange Detective and Super-Detective

Stories), this was a fresh market for Howard. Kline wrote of the spicies:

Your story “The Girl on the Hell Ship”

seems to be pretty close to what Frank Armer wants for Spicy Adventures, although it may not be quite hot enough for that

book. However, I am trying it on Armer and will let you know his reaction.

Price has done quite well writing for this magazine, as well as Spicy Detective. Perhaps he could give

you some good tips on this sort of thing if you are interested in following up.

Armer paid Price 1¢ a word for these yarns on acceptance. [...] No, I don’t

think anyone has any prejudice against your name; however, I do think it wise

for you to use a pen name on sexy adventure stories since you are identified

with the straight adventure and Western field under your own name. (IMH 31-32, OAK 1.4-5)

Howard successfully broke into with “She-Devil” under the

title “The Girl on the Hell Ship,” as by “Sam Walser,” which appeared in Spicy Adventure Stories Jan 1936. (IMH 371) With good news often came bad:

Wright reported that Magic Carpet

Magazine was definitely defunct, and would returned the unpublished Sailor

Dorgan yarns, and Margulies rejected “The Trail of the Bloodstained God” for Thrilling Adventures, with Kline

reporting:

Margulies recently wrote me that he

would not use chronicles of violent action, unless adequate attention was given

to plot conflict, motivation and character reaction. The theme of jewels, or

treasure secreted in an idol, jewel decorations for idols and idols with jewel

eyes has been done over and over so much editors are beginning to tire of it. I

have received a number of stories of this sort—some of them quite good—and have

been unable to place them because of editorial objections to this theme. The

story also is an odd length for many magazines, as it is neither a short story

nor a novelette. However, I’ll show it around—perhaps we can place it to your

advantage somewhere. (IMH 32, OAK 1.4-5)

|

Magic Carpet

July 1933 |

On the surface, 1935 was not the best year for Howard; by

the ledger (and Kline’s letter of 8 Oct 1935), Kline had managed to sell only

“Black Canaan” ($108.00), “The Last Ride” (a collaboration with Robert Enders

Allen, $78.75), “War on Bear Creek” ($54.00), “Weary Pilgrims on the Road”

($54.00), and “The Girl on the Hell Ship” ($48.60) for a total of $343.35 after

commissions. (IMH 367-371) However,

the ledger does not include all of Howard’s stories that were published that

year outside WT, including “The

Haunted Mountain,” “Hawk of the Hills,” “The Feud Buster,” “Blood of the Gods,”

“The Cupid from Bear Creek,” “The Riot at Cougar Paw,” “Boot Hill Payoff,” or

“The Apache Mountain War” so the total was undoubtedly higher—Howard probably

cleared closer to $600 through Kline’s agency in 1935.

Works Cited

BOD Book of the

Dead: Friends of Yesteryear: Fictioneers & Others

CL Collected

Letters of Robert E. Howard (3 vols. + Index & Addenda)

CS The Conan

Swordbook

FI Fists of

Iron (4 vols.)

IMH The Collected

Letters of Dr. Isaac M. Howard

MF A Means to

Freedom: The Letters of H. P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard (2 vols)

OAK OAK Leaves: The

Official Journal of Otis Adelbert Kline (16 issues)

WT50 WT50: A Tribute

to Weird Tales